At Techtide Solutions, we’ve lived through many codebases and release trains. Git’s architecture is more than convenience; it scaffolds modern software delivery. Budgets, tools, and ambitions are expanding. Worldwide IT spending is forecast to reach $6.08 trillion in 2026. Those funds mean more repositories, more contributors, and higher expectations for velocity and reliability. Here, understanding Git’s internals separates teams that use Git from teams that build on Git. Consider the commit DAG, the content-addressable object store, and the three-tier working model. We’ll share our foundations, real-world tradeoffs, and production patterns across industries.

Core principles powering git architecture

Git’s core principles were forged in the crucible of large‑scale, distributed development, and the lessons apply whether you’re shepherding a monorepo or dozens of service repositories. The sheer breadth of the developer workforce is a reminder of the pressure on tools to scale; the global population of software developers reached 28.7 million in 2024, and every one of those contributors leaves fingerprints in commit graphs, tags, and remotes that must remain trustworthy and comprehensible over time. When we teach Git to new teams, we start with principles, not commands, because the design choices explain the behaviors that often confuse day‑to‑day users.

1. Directed acyclic graphs for snapshots and merge history

Git’s history model is a directed acyclic graph (DAG) of commits, where each commit points to its parent commits and to a snapshot of the project state. The resulting graph isn’t an audit log in the accounting sense; it’s a living representation of how lines of development diverge and converge. The acyclic nature means we can reason about ancestry and causality without paradoxes: ancestry walks, blame analysis, and bisects all flow naturally from the graph’s structure.

Snapshots, not diffs

One of Git’s most consequential ideas is that each commit records a snapshot of the entire tree, not merely a diff. Through heavy deduplication in the object store, snapshots are stored efficiently, but conceptually they are complete states. This mindset leads to resilient operations in pathological scenarios: when files move or refactorings touch many paths, Git can still compute changes reliably because it compares snapshots rather than relying on fragile patch chains.

Merge semantics that encode decisions

In practice, a merge commit doesn’t merely glue two lines of work together; it encodes a decision about how competing edits were reconciled. That decision becomes part of the project’s institutional memory, reducing future rework when similar conflicts arise. We encourage teams to treat merge commits as narratives: the message should explain why a particular resolution was chosen—especially when intent is not obvious from the code—so future readers can replay the rationale.

Rewriting history with care

Commands that rewrite history—commonly used to produce a clean series of logical changes—are most useful before sharing work, because once commits propagate to others you risk diverging realities. Our house style is to reserve history editing for private branches and to prefer merges for public integration. This keeps the graph honest: your future self and your operations team will thank you when incident response involves clear ancestry rather than a memory exercise.

2. Content‑addressable storage with secure object IDs

Git turns content into identity. Blobs (file contents), trees (directory structures), commits, and tags are stored under IDs derived from content and metadata. Because identity flows from content, the same file materialized in two independent clones is the same object without coordination. That property unlocks efficient cross‑clone operations and robust deduplication: any time identical content appears, the object store recognizes it as the same thing. We see this pay dividends in monorepos where teams vendor common assets, in documentation repos that reuse images, and in binary‑heavy media projects that otherwise would bloat.

Why identity should come from content

File‑system paths are volatile: refactors, build tooling, and root‑level reorganizations can shift paths without changing substance. A content‑addressable design ignores path churn and focuses on what matters: if the content is identical, it’s the same object. That makes Git pipelines resilient in the face of moves and renames, and it enables precise caching strategies in CI/CD systems that hash inputs rather than tracking absolute paths.

Operational ergonomics from explicit identity

Object IDs give operators and developers a lingua franca for pinpointing the exact artifact in question—no ambiguity, no “which version did you mean?” We integrate IDs deeply into our review templates, release notes, and incident runbooks so every change is traceable to a stable reference. That habit reduces cycle time during rollbacks and root‑cause analysis.

Related Posts

3. Plumbing versus porcelain toolkit design

Git deliberately separates low‑level “plumbing” commands—which manipulate objects and references—from high‑level “porcelain” commands tuned for everyday workflows. This split encourages tooling to evolve without destabilizing fundamentals. In our client work, we often teach with plumbing to cultivate intuition, then codify porcelain‑like workflows with automation and guardrails. The result is a developer experience that feels simple while remaining grounded in precise, inspectable primitives.

When to drop down a level

When something “mysterious” happens—unexpected merges, surprising differences in status output—plumbing commands reveal the truth. Inspecting the exact tree a commit points to, writing an object by hand during a forensic exercise, or verifying which references map to which commit IDs eliminates guesswork. We find that even a little exposure to plumbing commands demystifies the porcelain and builds lasting confidence.

Inside the object database: Git objects and identity

Understanding Git objects is essential for building durable workflows. It’s also a practical necessity as code volume climbs. Teams adopting AI‑assisted coding tools generate and transform code faster, which means repositories evolve quickly; McKinsey observes that generative tools can reduce time spent on code generation by 35–45%, and those efficiency gains translate into more frequent commits, more branches, and more objects to manage. The antidote is clarity about what lives in the object store and how identity is determined.

1. Blob tree commit tag fundamentals

Git’s object taxonomy is small but expressive. Blobs are raw file content; trees are directory listings that reference blobs and other trees; commits reference a single top‑level tree and carry metadata like authorship and messages; tags point at any object to provide a human‑friendly veneer. That small vocabulary covers everything you need to represent a repository’s state and history. The elegance of the design is that each object’s ID is derived from its content and header, making identity both portable and tamper‑evident.

An author, a committer, and a message walk into a commit

A commit object records the state plus context: who authored the change, who committed it (often the same person, but not always), when it happened, and why. Those fields aren’t mere bookkeeping; we treat them as part of the team’s institutional knowledge. In regulated environments we recommend signed commits and tags, because cryptographic signatures raise the bar from “hard to tamper” to “provably attested by a specific key.”

Annotated tags over lightweight tags—most of the time

Tags are often used for releases. Lightweight tags are quick pointers; annotated tags carry a message and signature. In collaboration settings, annotated tags improve traceability, enabling clearer promotion flows across environments and providing durable anchors for SBOMs, provenance attestations, and rollbacks.

2. Creating and inspecting objects with hash‑object and cat‑file

Plumbing deepens intuition. You can write a blob directly and read it back: feed content into a hashing command to create an object, then inspect it through an object viewer. With a little practice, you can assemble a tree and even mint a commit by hand—helpful when reconstructing history after a mishap in a lab environment. We teach these exercises during enablement sessions; the payoff is that developers stop treating Git like a black box and instead see a transparent system with predictable behavior.

Forensics and learning by touch

When a build suddenly fails after a refactor, or a binary artifact appears to bloat a repo, object‑centric inspection answers questions: Is the file truly unique or a duplicate under a different name? Which commit first introduced it? How many downstream trees reference the same blob? By mapping these relationships, teams decide whether to purge history, migrate certain assets to LFS, or adjust code‑review rules to prevent future surprises.

3. Immutability and integrity guarantees across clones

Because identity is content‑based, the same commit in two independent clones is literally the same object. That immutability gives distributed history its strength: audits, provenance checks, and replayed analyses yield identical results, assuming no tampering. Integrity verification tools walk the object graph, recomputing IDs and verifying that object headers and contents match expectations. In our experience, teams that integrate these checks into CI stop many repository‑level issues long before they reach production—especially in environments with multiple remotes or mirrored repositories.

Sign what matters

For high‑assurance pipelines, we advise signing release commits and tags. Combined with protected branches and pre‑receive policies, signatures provide strong guarantees that a particular release artifact originates from a known process and has not been altered. That stance supports audit readiness, zero‑trust principles, and customer trust in distributed ecosystems where artifacts flow across organizational boundaries.

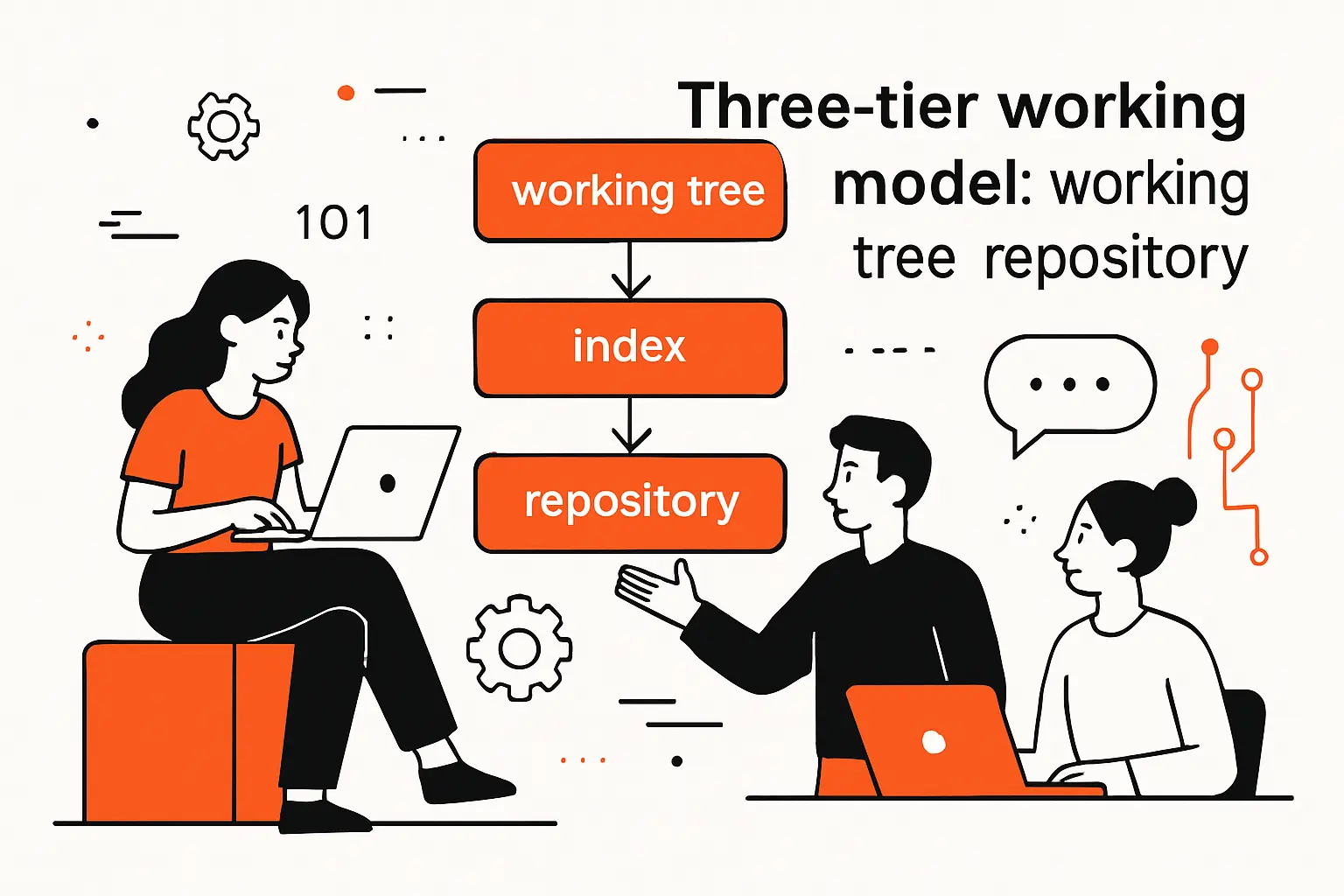

Three‑tier working model: working tree index repository

Git’s three‑tier model—working tree, index, repository—is a gift to teams that care about clarity. The model shines in heterogeneous infrastructure, where code moves among laptops, build farms, and cloud environments; multicloud is the norm, with 93% of organizations using multiple cloud providers. That diversity means the same repo will be touched by many tools and processes, making it even more important to understand how edits flow from the filesystem to staged changes and finally into the immutable object store.

1. Working tree edits and untracked changes

The working tree is your sandbox. Editors and build tools write files freely; Git watches passively. Some files don’t belong under version control—runtime logs, local environment files, transient build outputs. We encourage teams to maintain separation of concerns: encode ignore patterns in project‑level ignore files, and reserve personal ignore lists for truly private artifacts. That discipline prevents accidental seepage of environment‑specific files into history and stabilizes the build process across machines.

Guardrails for local experiments

We coach developers to create a scratch branch when they want to explore ideas, combine that with stash‑like workflows for context switches, and adopt pre‑commit checks that run quickly and locally. Those guardrails support curiosity without risking pollution of shared history. In incident response, being able to isolate and clean up scratch changes is often the difference between a short interruption and a prolonged outage.

2. Staging index for selective structured commits

The index is a curated interface between messy reality and a clean history. It’s where you assemble a logical change set from a sea of edits. Selective staging lets you extract a minimal, coherent commit from a working directory full of experiments. We emphasize this muscle in code‑review culture: reviewers appreciate commits that tell a clear story, and small, tightly scoped changes travel through CI/CD systems with fewer surprises. Selective staging is not just convenience; it’s a reliability technique.

Shaping history with intention

When teams practice structured commits, downstream systems benefit. Build caches become more effective when changes are tightly focused, bisecting becomes humane, and rollback strategies become straightforward because each commit corresponds to a single intent. We’ve seen teams cut incident resolution time simply by adopting consistent commit hygiene that the index makes possible.

3. Repository internals object store and refs plus remotes for collaboration

The repository is where the durable truth lives: objects, references, and configuration. References name points in history; remotes map those references to other repositories. Most collaboration flows boil down to a safe dance of fetching references, integrating changes, and pushing updates under agreed‑upon rules. We configure branch protections at the server and augment them with pre‑receive hooks that validate commit messages, tag formats, and signatures. The result is a system where collaboration is unconstrained but still governed by predictable, auditable policies.

Remote choreography

In multi‑remote setups—common in regulated industries or companies with layered deployment rings—we teach teams to treat each remote as a contract. What references are mirrored? Which branches are authoritative? Where are tags allowed to originate? By formalizing these relationships, you avoid conflicts that surface at the worst moments, like during a hotfix or an emergency rollback.

References branches and HEAD in git architecture

References are the signposts that make the object store navigable. The bigger the engineering organization, the more important it becomes to shape reference conventions that scale. That need has only intensified as tech budgets ramp; worldwide IT spending is expected to total $5.43 trillion in 2025, and expansion tends to multiply repos and environments. Clear reference policies prevent that growth from devolving into entropy.

1. The refs namespace for heads and tags

Under the hood, references live in a structured namespace. Heads represent active branches; tags name specific commits or other objects. Lightweight tags behave like nicknames, while annotated tags function more like signed letters. We default to annotated tags for anything that might gate compliance, releases, or backporting workflows, reserving lightweight tags for ephemeral local use.

Designing for longevity

Reference names live longer than we expect. We recommend descriptive namespacing that groups references by function—release, environment, or program—and linting rules that prevent accidental collisions. Over time, such conventions reduce friction as the number of branches grows and as teams change.

2. Branches as movable pointers to commits

A branch is simply a pointer that moves forward as you commit. That simplicity empowers branching strategies that fit your release cadence: long‑lived stable branches for products with extended support horizons, trunk‑oriented flows for rapid iteration, or hybrid models in between. We advise aligning branch strategy with the source of truth for releases: if releases are cut from a mainline, protect that branch heavily; if they’re cut from named release lines, invest in automated back‑merges to minimize drift.

Naming for intent, not convenience

We’ve watched teams struggle with ambiguous names whose meanings mutate over time. A small investment in naming—embedding intent and scope—pays off in the long run. Turning branch names into living documentation keeps the DAG understandable and sanity‑checks automation that filters by patterns.

3. HEAD checkout and how the index and working tree update

HEAD is your current view into the graph. Checking out a commit or a branch means aligning the index and working tree to that reference. Understanding this triad prevents surprises: if a file is modified locally but not staged, switching context will either carry those changes or refuse to proceed, depending on conflicts. We encourage teams to adopt a rhythm of saving work, staging intentionally, and switching contexts only when the working tree is clean—or at least aligned with expectations.

Detached doesn’t have to mean dangerous

Working in a detached state is safe when you know what you’re doing. We use it for bisects, forensics, and quick experiments that we later anchor to a named branch if they prove useful. The key is to understand what HEAD represents at each step, so useful work isn’t lost to garbage collection or overwritten by mistake.

Efficient storage and distribution

Git’s design wouldn’t matter if storage and distribution couldn’t keep up with modern scale. Demand is growing across ecosystems; spending specific to artificial intelligence alone is expected to total $1.5 trillion in 2025, and that surge shows up as larger repositories, more generated assets, and higher expectations for CI throughput. Efficient storage structures and a smart pack protocol are what keep cloning, fetching, and artifact generation practical under those conditions.

1. Loose objects versus packed objects

When you first create objects locally, they are loose—one file per object. Over time, maintenance consolidates them into packfiles for space efficiency and faster transfer. The combination offers flexibility for edits and speed for distribution. In practice, we tune maintenance schedules to the team’s cadence: batch compaction when developers are offline, and incremental housekeeping after bursts of activity. For repos with hefty media, we weigh the merits of large‑file extensions, careful ignore policies, and artifact offloading to specialized storage.

Pragmatism in big repos

We’ve helped media and gaming teams tame repositories that would otherwise crawl. The trick is to match asset workflows to Git’s strengths: store what benefits from Git’s deduplication and history, push bulky build outputs to artifact stores, and use dependency pinning rather than in‑repo vendoring when upstreams already provide deterministic fetches. The fastest clone is the one you don’t have to perform repeatedly.

2. Packfile indexes checksums and corruption detection

Packfiles group related objects and encode deltas to compress history. Index files accelerate lookups, and checksums make corruption evident. We integrate verification into CI to catch issues early and use server‑side policies to reject suspicious pushes. It’s also good operational hygiene to capture the exact packfiles associated with a release for auditing and reproducibility. That record makes it easier to explain to auditors—or future teammates—why an artifact is exactly what it claims to be.

Trust, but verify automatically

Human error is inevitable, so we shift integrity verification left. Automation that validates pack integrity, signatures, and reference updates at push time prevents subtle problems from becoming outages. This is especially valuable in environments that mirror repositories across regions or vendors, where transient network issues can produce partial state without careful checks.

3. On‑the‑fly packfiles for network synchronization

Git’s network protocol negotiates exactly which objects are missing on the other side, then generates packfiles on the fly for efficient transfer. The protocol supports thin packs and partial clones to reduce payloads even further. We routinely deploy sparse‑checkout and partial‑clone strategies for monorepos so teams can work on relevant subsets while still preserving the integrity of the history. Pair these features with artifact caching in CI and you get faster feedback loops without sacrificing reproducibility.

Negotiation as a performance lever

When a repository’s history grows, the default negotiation may not be optimal for your topology. We profile fetch and clone flows, then adjust server settings and client flags to accelerate common paths. The payoff is measurable in developer satisfaction: shorter wait times mean more time in flow and fewer context switches.

How TechTide Solutions helps you build on git architecture

Software strategy should align with market realities. Venture funding shapes which tools and platforms will evolve fastest, and it has been resurging; global venture funding rose to $121B in Q1’25, with a concentration in infrastructure and AI that will influence developer tooling. Our role is to translate those macro shifts into pragmatic Git practices that make your teams faster and your releases safer.

1. Custom solutions aligned with your branching and release workflows

Branching strategy is policy encoded as pointers. We start by mapping your release cadence, regulatory constraints, and operational risk appetite. From there we co‑design a branching model: perhaps trunk‑oriented with frequent release tags and automated promotion, or a release‑branch model with hardening periods and forward‑merge automation. We then build the guardrails: protected branches, required reviews, signed tags, and pre‑receive hooks that enforce your conventions without developer friction. In one financial‑services engagement, we replaced brittle, ad‑hoc branching with a clear flow tied to risk tiers; the next incident arrived with less drama because a deterministic rollback path existed by design.

Merges, rebases, and the human factor

We coach teams not as a rules police but as stewards of intent. Rebases are great before sharing to maintain clean series; merges shine when two lines of work meet publicly and should signal that fact. We also embed templates for commit messages: problem statement, approach, and scope. That small habit halves the time reviewers spend trying to infer intent and improves the signal in code search and archeology.

2. Repository design migration and standardization for teams

We’ve moved teams from centralized version control to Git, split monoliths into repos that match ownership boundaries, and consolidated fractured repos into monorepos when integration pain exceeded the value of isolation. The right direction depends on your architecture and culture. Where binary assets are essential, we stage a path to large‑file solutions and artifact stores. When history is noisy, we plan surgical rewrites with quarantines and backups. And when compliance is strict, we layer in signed commits, reproducible build manifests, and release attestation policies that stand up to audits.

Standardize what matters; leave room for autonomy

Every team wants some autonomy; operations wants fewer surprises. We create standards for what truly benefits from uniformity—branch names, tag rules, review requirements—while allowing local preferences for editor, shell, and everyday ergonomics. That division respects developer craft without compromising the system’s predictability.

3. Automation CI CD hooks and developer enablement

Automation converts good intentions into reliable practice. We wire up pre‑commit checks that are fast enough to be habit‑forming, server‑side validators that prevent invalid references from landing, and CI pipelines that treat Git objects as the source of truth. We then teach the why, not just the how: plumbing commands for forensics, partial‑clone techniques for performance, and reference hygiene that keeps history readable. The goal is a system where developers move quickly because the rails keep them on track—and where audits are boring because the evidence is built into the workflow.

Measure friction, not just throughput

We instrument the developer experience: time to first review, time from approval to release, and time lost to avoidable conflicts. Those signals guide targeted improvements—perhaps widening merge windows, adjusting cache strategies, or refining branch protection to fit real‑world rhythms. By treating Git as an operational substrate, not a mere tool, we make measurable improvements to both speed and reliability.

Conclusion: what to remember about git architecture

Zooming out, the forces reshaping software—AI‑assisted coding, distributed infrastructure, and shifting funding patterns—magnify the value of Git’s fundamentals. As budgets rise and toolchains evolve, we keep returning to the same core idea: Git turns change into an inspectable, immutable narrative. That narrative powers everything from risk management to developer happiness. If you understand the architecture, you can shape the story deliberately.

1. Objects DAGs and refs form the foundation

Blobs, trees, commits, and tags are compact building blocks. The commit graph captures the real history of collaboration, not just the order of events, and references provide the stable handles we need to navigate and automate. When we design workflows, we do it in the language of objects and refs, because that’s what the system truly understands.

2. The three‑tier model enables precise staging and history

Working tree for exploration, index for intent, repository for truth: that separation is a gift to reliability. It allows developers to shape changes before they become history and to stage just enough to tell a coherent story. When applied consistently, the result is cleaner reviews, faster builds, and smoother releases.

3. Compression and distribution support scale and collaboration

Efficient storage and smart network negotiation keep Git fast even as repositories and contributor counts grow. Packfiles, verification, and partial‑clone techniques make it feasible to maintain realism in CI and sanity on laptops. When every object can be traced, verified, and moved efficiently, collaboration scales without losing integrity.

We’ve helped teams of many shapes and sizes lean into these principles to improve delivery and reduce operational risk. If you’re ready to turn Git from a daily habit into a strategic advantage, let’s map your repository architecture and branch strategy to your release goals—what’s the one friction point you’d most like us to remove first?