At TechTide Solutions, we treat voice technology as more than a “talk to your device” novelty; it is an interface layer that collapses friction between human intent and digital execution. Voice is fast, socially natural, and often available when hands and eyes are busy—on a warehouse floor, inside a moving vehicle, or in the middle of a patient intake conversation. Yet, the magic that users feel (“it just understands me”) is built on a very real engineering pipeline: audio capture, signal conditioning, statistical inference, language understanding, action execution, and response generation, all wrapped in privacy and reliability constraints.

For business leaders, voice sits at an uncomfortable intersection: it is simultaneously one of the most accessible interfaces and one of the most sensitive data channels. That tension is why we like to ground strategy in market reality rather than hype. As a quick market overview, Statista projects the Speech Recognition market in the Americas will reach US$3.26bn in 2025, a useful signal that buyers continue funding speech-driven products even as the AI landscape shifts.

In the sections below, we walk through what voice technology is, how it works end-to-end, where it fails in the real world, and how we build production systems that respect users while delivering measurable business value.

What is voice technology? Definition and where it shows up

1. Voice-based interaction: using spoken language and commands to control devices and services

Voice technology is the set of software and hardware techniques that let people use spoken language as an input method, and sometimes as an output channel, to control devices and services. From our perspective at TechTide Solutions, the core promise is simple: translate messy human speech into an actionable representation a system can execute—an intent, a command, a query, or a structured transaction.

Behind that promise, the “interaction” part matters as much as the “speech” part. A smart home command (“turn on the lights”) is not merely transcription; it is a state change in an IoT graph. A customer-service call is not merely recognition; it is a dialogue that must route, verify, and resolve, with escalation paths when confidence drops. Good voice design therefore includes conversational flows, confirmations, repair strategies (“did you mean X or Y?”), and clear fallbacks when the user’s request is ambiguous.

Where we see the biggest product wins

In real deployments, voice tends to win when speed and convenience beat precision typing. Field service notes, hands-busy workflows, and quick “micro-actions” inside an app often deliver the fastest ROI because users feel the time savings immediately and adoption becomes self-reinforcing.

2. Hands-free, natural communication that reshapes how humans and computers exchange information

Hands-free interaction changes the geometry of computing. Screens require attention, posture, and fine motor control; voice requires audibility, turn-taking, and trust. That tradeoff reshapes product requirements: latency becomes experiential (a pause feels like confusion), error handling becomes conversational (a correction must be easy), and privacy becomes visceral (a device that is “listening” changes behavior).

From our build experience, the “natural” in natural language is not achieved by sounding human; it is achieved by respecting human conversational norms. Users expect acknowledgments, clarification when needed, and continuity across turns (“Book it for tomorrow” after discussing a meeting). They also expect a graceful exit. A voice interface that cannot gracefully say “I can’t do that yet” tends to erode trust faster than a UI button that simply doesn’t exist.

Why voice feels different from chat

Text chat supports skimming, editing, and copy/paste. Speech is ephemeral. That reality pushes engineers to build for confirmations, summaries, and “read-back” patterns, especially in domains like healthcare, finance, and logistics where a misheard value can become an expensive mistake.

Related Posts

- How to Build RAG: Step-by-Step Blueprint for a Retrieval-Augmented Generation System

- How Does AI Affect Our Daily Lives? Examples Across Home, Work, Health, and Society

- Real Estate AI Agents: A Practical Guide to Tools, Use Cases, and Best Practices

- What Is AI Integration: How to Embed AI Into Existing Systems, Apps, and Workflows

- Customer Segmentation Using Machine Learning: A Practical Outline for Building Actionable Customer Clusters

3. From consumer tools to business deployments across customer care, healthcare, and transportation

Voice technology shows up everywhere precisely because speech is universal. Consumers meet it through smartphone assistants, smart speakers, earbuds, and dictation keyboards. Enterprises meet it through contact center automation, transcription, voice analytics, and voice-controlled industrial devices. Transportation adds another pressure: safety, where voice becomes a surrogate for touch.

Scale is no longer hypothetical. Juniper Research reported that consumers will interact with voice assistants on over 8.4 billion devices by 2024, which is less about smart speakers and more about voice becoming a default capability embedded into phones and everyday endpoints.

A pattern we see in regulated industries

In healthcare and transportation, teams often begin with “assistive voice” rather than “autonomous voice.” Dictation, read-back, and guided workflows provide value while keeping a human in the loop, which reduces risk and makes compliance reviews far smoother.

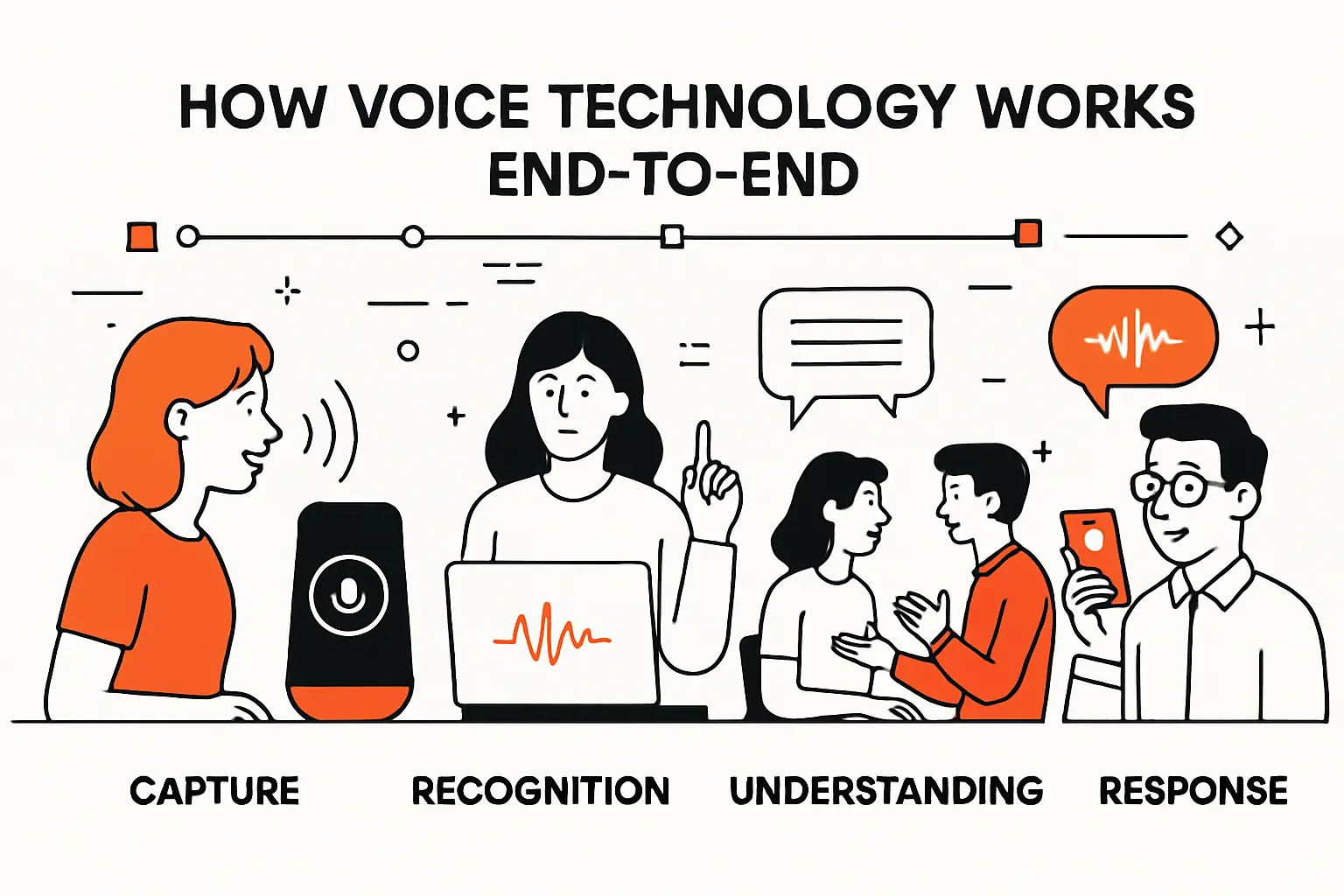

How voice technology works end-to-end: capture, recognition, understanding, and response

1. Voice capture and audio pre-processing to reduce noise and improve signal quality

Every voice system starts with physics: sound waves hit a microphone, become an electrical signal, and are digitized into audio frames. Product teams often underestimate how much “voice AI” performance is won or lost before a model ever runs. Microphone placement, device materials, cabin acoustics, and far-field reverberation can dominate perceived accuracy.

In production systems, we typically apply a chain of preprocessing steps: automatic gain control, echo cancellation (especially when the device is playing audio), noise suppression, and voice activity detection to segment speech from silence. Far-field devices rely heavily on beamforming when multiple microphones are available, steering sensitivity toward the speaker while suppressing background sources. Even a great model can fail if the input signal is clipped, over-suppressed, or drowned in non-stationary noise like clattering dishes or machinery.

Wake word vs. open mic

Most consumer devices run a wake-word detector as a low-power gate before higher-cost recognition. In enterprise deployments, we often choose push-to-talk or explicit activation inside an app to reduce accidental capture and simplify privacy messaging.

2. Feature extraction and pattern matching to convert speech into text or structured intent

After capture, the system needs a representation that machine learning models can work with. Classic pipelines compute spectral features (often log-mel style representations) that capture how energy is distributed across frequencies over time. Modern neural systems sometimes learn features directly from waveforms, yet the underlying goal stays the same: compress raw audio into something that makes phonetic patterns separable.

Automatic speech recognition (ASR) models then map those features into tokens—characters, subword units, or words—using architectures that have shifted over time from HMM-based hybrids to end-to-end neural networks. In our engineering reviews, we focus less on the buzzwords and more on operational behavior: streaming vs. batch decoding, on-device vs. cloud inference, how confidence is calibrated, and how the system behaves when the user self-corrects mid-utterance.

“Intent-first” designs

For constrained domains (like checking an order status), structured intent classification can outperform full transcription because the system only needs to distinguish a small set of actions. That approach often improves reliability and reduces the chance of hallucinated “extra” words affecting downstream logic.

3. Language processing and response generation to execute actions and deliver answers

Recognition produces text (or tokens), but users want outcomes. Natural language understanding (NLU) typically classifies intent and extracts slots (entities like names, dates, locations, product identifiers), then passes structured data into business logic. Dialogue management decides what to do next: ask for missing information, confirm a risky action, or execute immediately.

At TechTide Solutions, we treat response generation as both a UX surface and a safety mechanism. A well-designed response can prevent costly errors by repeating key details (“Scheduling the pickup for Friday at the loading dock—correct?”) and by offering bounded choices rather than open-ended prompts. When generative models are involved, we add guardrails: retrieval constraints, policy filters, and deterministic action layers that prevent the model from “making up” system states it cannot verify.

Action execution is where voice meets reality

Once an intent resolves, the system must call APIs, update records, trigger IoT actions, or create tickets. Failures here are common—expired tokens, rate limits, missing entitlements—so we design conversational recovery (“I couldn’t reach your calendar—want to try again?”) rather than dead ends.

4. Voice-to-voice systems: speech recognition, machine translation, and speech synthesis

Voice-to-voice systems add two more transformations: translation and synthesis. The pipeline becomes: speech-to-text (or speech-to-meaning), translation into a target language, and text-to-speech (TTS) to speak the output. Each step introduces latency and potential semantic drift, so end-to-end evaluation must measure not just transcription quality, but whether the final spoken output preserves user intent.

Synthesis has evolved from concatenative approaches to neural TTS that can produce expressive prosody. That progress is a double-edged sword. On one hand, it enables accessible voices, branded assistants, and smoother customer experiences; on the other, it raises the stakes for impersonation and voice cloning abuse. When we build voice-to-voice features, we therefore treat “what should be said” as a governed artifact, not a creative afterthought.

Latency budgets matter more than model size

In conversational systems, long pauses feel like failure. We frequently optimize for streaming partial results, incremental synthesis, and edge inference because perceived responsiveness drives adoption more than marginal accuracy gains in a lab setting.

Voice recognition vs speaker recognition: understanding words vs identifying speakers

1. Voice recognition for dictation, commands, and converting speech into written text

Voice recognition usually means speech recognition: converting a person’s spoken words into text or commands. Dictation in a document editor, voice search in a mobile app, or “set a reminder” on a smart speaker are all examples where the system’s job is to understand content, not identity.

From an engineering standpoint, speech recognition is hard because language is open-ended. Accents vary, vocabulary shifts by domain, and speech is full of false starts and repairs. Production-grade systems manage this messiness with domain adaptation, custom vocabularies, contextual biasing (for names or product terms), and careful post-processing that preserves meaning while normalizing punctuation and formatting. When teams skip these “unsexy” steps, accuracy complaints often show up as product churn rather than as a neat bug report.

Dictation is not the same as commands

Dictation optimizes for fidelity and punctuation, while command interfaces optimize for intent resolution and safe action execution. Mixing the two without clear UX signals is a reliable way to confuse users and create brittle edge cases.

2. Speaker recognition and voice biometrics for authentication and customer verification

Speaker recognition answers a different question: “Who is speaking?” rather than “What are they saying?” Voice biometrics systems learn speaker characteristics and compare incoming speech to an enrolled voiceprint, often supporting verification (claiming an identity and checking it) or identification (searching a population).

We approach voice biometrics cautiously. In high-friction workflows—like contact center authentication—voice can reduce repeated security questions and shorten handle times. At the same time, voice is not a secret; it is broadcast in public spaces and recorded in countless contexts. Any authentication strategy built on voice should include anti-spoofing controls, risk-based step-ups, and clear user consent patterns. For teams wanting a rigorous grounding, we point to NIST’s systematic evaluations of speaker recognition technology as the kind of measurement discipline the industry needs more of.

Voiceprints are sensitive data

A voiceprint is not just another identifier; it is a biometric proxy. Storage, retention, and deletion policies must be designed up front, because retrofitting governance after rollout tends to be painful and credibility-damaging.

3. Key constraints: vocabulary and computing limits, background noise, and words that sound alike

Real-world voice systems live under constraints that product demos politely ignore. Vocabulary coverage matters: a general model may struggle with industry jargon, part numbers, medication names, or multilingual code-switching. Computing limits matter as well, especially on embedded devices where power and memory budgets force tradeoffs between on-device privacy and cloud-level capability.

Noise remains the evergreen enemy. Background audio, multiple speakers talking over each other, and echo from a device’s own speaker all degrade performance. Homophones and near-homophones create failure modes that are uniquely frustrating because the system “heard something plausible,” just not what the user meant. For business workflows, we mitigate this with confirmation patterns on high-impact fields, structured slot capture (spelling or digit grouping when appropriate), and environment-specific tuning rather than one-size-fits-all models.

Confidence is a product feature

A useful system knows when it does not know. Calibrated confidence scores let us route uncertain cases to clarification or to a human, which usually matters more than chasing a slightly better benchmark score.

Voice assistants and smart speakers: major platforms and common capabilities

1. Google Assistant: natural-language tasks, app actions, and smart home control

Google Assistant’s strength has historically been broad knowledge queries and strong language handling, supported by Google’s search and ecosystem integration. In practical use, that means high-quality answers for general questions, plus useful device control patterns that connect to a wide range of smart home platforms and third-party services.

From an enterprise integration angle, we think of Google’s assistant ecosystem as a set of surfaces and capabilities rather than a single product. The real design question becomes: should a business build a branded assistant experience, integrate with an existing platform, or embed voice inside its own mobile app where identity and context are already known? In many cases, the simplest path to value is not “become a voice destination,” but “make our existing workflow voice-accessible where it already lives.”

Where Google-style assistants shine

Complex queries, multilingual contexts, and knowledge-heavy interactions tend to be strong fits. Conversely, regulated workflows often require stricter conversational guardrails than consumer assistants are designed to enforce by default.

2. Amazon Alexa: cloud-based assistant powering smart speaker and device ecosystems

Amazon Alexa is often synonymous with smart speakers, but its larger impact is the device ecosystem it helped normalize: wake words, voice-driven routines, and “skills” as a distribution model for voice experiences. For consumers, that ecosystem reduces setup friction; for businesses, it creates an expectation that devices should be controllable by voice without custom UI work.

In IoT-heavy projects, we treat Alexa-like patterns as a reference architecture: discover devices, model them as capabilities, then expose predictable commands with clear feedback. The engineering caveat is that cloud-based assistants introduce dependency chains—connectivity, service health, third-party APIs—that product teams must account for with graceful degradation. In our experience, the most resilient designs keep local control paths for critical functions even when cloud assistants are available.

Skills are product surfaces, not just integrations

A voice “skill” needs the same care as an app screen: clear prompts, tight error handling, and a predictable personality. When those pieces are missing, abandonment happens quickly because voice interaction has a lower tolerance for confusion.

3. Apple Siri: voice assistant adoption and multilingual support across Apple devices

Siri matters because it rides inside a tightly integrated hardware and software ecosystem. That integration allows consistent invocation across devices and makes voice feel like a default capability rather than an add-on. For teams building iOS experiences, Siri can be a distribution channel through system-level entry points, but it can also be a constraint if a workflow requires more control than system intents allow.

Privacy posture is a central differentiator in Apple’s messaging, and we respect the product implication: users are more willing to speak when they believe they are not being profiled. Apple describes Siri as designed to do as much processing as possible right on a user’s device, which aligns with what we see as a broader market trend toward edge inference for sensitive interactions.

Multilingual is more than translation

True multilingual support involves locale-aware formatting, culturally appropriate phrasing, and handling of bilingual speech patterns. A system that merely translates words can still fail at intent because meaning is contextual.

4. Automotive voice systems: hands-free voice control for safer driving and in-car tasks

Automotive voice systems are where voice’s promise meets harsh conditions: road noise, multiple passengers, intermittent connectivity, and real consequences for distraction. That environment pushes design toward constrained, high-confidence tasks like navigation, calling, media selection, and climate control, with strong confirmation behaviors for anything safety-relevant.

In vehicle contexts, we recommend designing for interruption and partial attention. Drivers speak in fragments, change their minds, and expect the system to keep up without a rigid command grammar. The technical response is typically a combination of robust noise suppression, fast streaming recognition, and dialogue flows that can recover from mid-sentence corrections. The product response is equally important: reduce verbosity, keep prompts short, and never punish the user for speaking naturally.

The “eyes-free” contract

If a system forces drivers to look at a screen to fix a voice error, it has already failed the core safety goal. Our automotive-oriented builds always include voice-only correction pathways and minimal-cognitive-load confirmations.

Voice technology implementations across the IoT landscape

1. Smart homes: voice hubs as a single interface for connected device management

Smart homes are the most visible IoT+voice pairing because they solve a real coordination problem: too many apps for too many devices. A voice hub becomes the “single pane of intent,” letting users express outcomes (“dim the living room lights”) instead of navigating vendor-specific controls.

From an engineering standpoint, the hard part is not speaking; it is orchestration. Devices must be discovered, represented in a consistent capability model, and kept in sync with actual state. We design smart home voice layers around a normalized device graph with clear idempotent actions (so repeating a command is safe), plus state reconciliation when devices go offline or report conflicting data. Without that plumbing, voice becomes a thin veneer over chaos.

Scenes and routines are where value compounds

Users rarely care about single-device commands after the novelty phase. The sticky value comes from multi-device routines—lighting, security, media, and climate shifting together—because that is where voice saves real time.

2. Digital workplace: voice-enabled productivity, scheduling, and speech-to-text meeting support

In the digital workplace, voice shows up less as a “talking assistant” and more as an ambient capture and retrieval layer: meeting transcription, action-item extraction, searchable audio notes, and hands-busy dictation. Adoption tends to be highest when voice features remove tedious work rather than attempting to replace knowledge workers’ judgment.

When we implement workplace voice, we focus on workflow integration. A transcript that lives in isolation is a novelty; a transcript that links to tickets, documents, or CRM records becomes operationally meaningful. Accuracy tuning in this context is usually domain-driven: names, acronyms, and project terms matter more than generic vocabulary. Security design matters as well, because meetings often include sensitive data that must be access-controlled and retention-governed.

Searchable knowledge beats perfect transcripts

Teams often chase verbatim accuracy when the real business value is findability: being able to locate decisions, owners, and deadlines quickly. We therefore design for indexing, highlights, and structured summaries that users can verify.

3. Voice payments: conversational agents and voice biometrics for touchless financial experiences

Voice payments are appealing because they promise a no-touch transaction flow: order, confirm, and pay without typing. Consumer appetite exists, but trust is the limiting reagent. PwC’s consumer research reports 50% of respondents have made a purchase using their voice assistant, a strong signal that “voice commerce” is real even if it remains uneven across product categories.

In payment-adjacent systems, we prefer a layered approach: voice for initiation and navigation, then a secure step for authorization. That step might be device-based authentication, a confirmation in an app, or a risk-based challenge depending on transaction context. Voice biometrics can contribute, but we rarely recommend it as a standalone gate; instead, it becomes one signal among many in a broader fraud and identity strategy.

Design for “accidental purchases”

Voice interfaces are prone to unintended activation and mishearing. Clear confirmations, cancellation windows, and transaction summaries protect both customers and brands from avoidable disputes.

4. Industrial IoT: hands-free workflows, plus noise, language, and accent requirements

Industrial IoT is where voice can be genuinely transformative because it meets users in environments where touchscreens are impractical: gloves, grease, ladders, forklifts, or sterile conditions. The best use cases are often procedural—checklists, inspections, pick-and-pack confirmations, and “what’s next?” prompts—where voice reduces context switching and keeps attention on safety.

Noise and multilingual realities are non-negotiable in these settings. We build with environment-specific audio profiles, push-to-talk patterns when wake words are unreliable, and command sets that tolerate accent variability without becoming ambiguous. Organizational success depends on change management too; frontline teams adopt voice when it respects their pace and when errors are treated as system responsibilities rather than worker failures.

Edge-first architectures often win

Factories and warehouses frequently have dead zones and network constraints. On-device recognition for a bounded vocabulary, with periodic sync to cloud systems, can outperform a cloud-only design in both reliability and user trust.

Business applications of voice technology: customer experience, analytics, and operations

1. Intelligent virtual agents: always-on self-service and personalized follow-ups

Intelligent virtual agents (IVAs) in voice channels aim to resolve common requests without human intervention while still feeling conversational. In contact centers, that often means handling identity checks, order status, appointment scheduling, policy questions, and routing—then escalating gracefully when the request is complex or emotionally charged.

At TechTide Solutions, we frame IVAs as customer experience infrastructure, not as cost-cutting bots. The business value arrives when customers get faster outcomes and agents receive cleaner context when escalation happens. Implementation success typically hinges on tight integration with backend systems, careful intent scoping, and honest prompts that set expectations. When an IVA pretends to be smarter than it is, callers punish the brand, not the model.

Personalization must be earned

Using CRM context can create delightful “welcome back” moments, yet it also increases privacy sensitivity. We recommend progressive disclosure: start helpful, then become more personalized as the user explicitly opts into convenience features.

2. Voice data analytics: intent and sentiment signals to improve products and customer care

Every voice interaction is also a dataset: what customers ask for, where they get stuck, what phrases precede escalation, and what sentiment patterns predict churn. Voice analytics turns that raw stream into product intelligence by tagging intents, extracting themes, and identifying friction points across journeys.

Operationally, the challenge is connecting speech-derived insights to business levers. A dashboard that says “customers are frustrated” is not actionable by itself. Instead, we design analytics pipelines that map utterances to specific policy gaps, UX failures, or knowledge-base issues, then feed those insights into product backlogs and training loops. Governance matters here too, because analytics often requires retention of transcripts or audio, which must be handled with clear purpose limitation and access controls.

Measure outcomes, not model scores

Word-error metrics are useful engineering signals, but businesses feel resolution rates, time to completion, and complaint reduction. Our analytics approach ties voice performance to those operational metrics so optimization priorities stay grounded.

3. Transcription and dictation: faster documentation for meetings, interviews, and clinical notes

Transcription is one of the most immediately valuable voice applications because it compresses time spent documenting into time spent thinking. Teams use it for meeting notes, interviews, field reports, and clinical documentation, with the biggest gains often appearing where documentation is both mandatory and time-consuming.

Engineering realities still apply. Domain vocabulary must be supported, diarization must handle multiple speakers, and formatting must fit the destination system (a ticket, a note, a report). In healthcare-adjacent contexts, we build with explicit review steps so clinicians can verify content before it becomes part of a record. That “verify before finalize” loop is not a barrier; it is a trust accelerator that prevents rare errors from becoming systemic fear.

Structured output beats raw text

For operational documentation, teams frequently want problems, actions, owners, and next steps, not a wall of text. We therefore add extraction layers that propose structure while keeping the original transcript available for auditability.

4. Custom digital voices: consistent brand experiences across channels and touchpoints

Custom digital voices let organizations create a consistent sonic identity across phone systems, in-app assistants, kiosks, and embedded devices. When done well, the result is not gimmicky; it feels like a coherent extension of the brand’s tone, accessibility posture, and service philosophy.

Risk management is essential. Voice cloning and synthetic speech can blur ethical boundaries if consent and usage scope are unclear. We advocate for explicit contracts around who a voice represents, where it can be used, and how it is protected from misuse. That discipline aligns with the broader economic push toward automation: McKinsey estimates generative AI could add $2.6 trillion to $4.4 trillion annually in value, and branded voice experiences are one of many ways companies try to capture that value without degrading customer trust.

Brand voice is also a QA problem

Consistency requires a style guide: pronunciation rules, pacing norms, empathy language, and escalation phrasing. Without that guide, different teams ship different “voices,” and the experience fractures across channels.

Benefits and risks of voice technology for users and organizations

1. Productivity and cost impact: multitasking, reduced handling time, and operational savings

Voice is a productivity tool when it reduces context switching. A nurse can dictate while moving between tasks. A driver can control navigation without hunting through menus. A support agent can retrieve information without breaking conversation flow. Those micro-savings accumulate into real operational impact when scaled across teams and time.

Cost savings can appear, but we avoid selling voice purely as a cost play. In our experience, the best returns come from higher throughput and better outcomes—faster resolution, fewer repeat contacts, and less rework due to missing documentation. Voice also shifts where labor is spent: less time on routine capture, more time on judgment and empathy. Organizations that plan for that shift, rather than pretending it does not exist, usually get the healthiest long-term results.

Automation without empathy backfires

When a voice system blocks customers from reaching a human, it becomes a brand liability. We design for “fast self-service” and “fast escalation,” treating both as productivity features.

2. Accessibility and ease of use: hands-free interfaces that reduce barriers to technology

Accessibility is one of the most compelling reasons to invest in voice. Users with mobility limitations, vision impairments, temporary injuries, or situational constraints can often complete tasks by speaking when typing is difficult. Voice also supports literacy and language diversity when systems are designed with inclusive prompting and tolerant recognition.

From our perspective, accessibility is not only altruism; it is product resilience. Interfaces that work in more contexts reduce abandonment and expand the reachable user base. The key is to design beyond the happy path: provide alternatives to voice when speech is not possible, support clear correction mechanisms, and respect the user’s control over when the microphone is active.

Inclusive design starts with diverse data

Accents, dialects, and speech differences should be present in testing, not discovered after launch through angry support tickets. We push clients to treat diversity in evaluation as a release criterion, not a future improvement.

3. Privacy and security concerns: voice data collection, voice prints, and user trust challenges

Voice data is intimate. It can reveal identity cues, emotional state, health context, and household dynamics, even when transcripts remove obvious identifiers. Users therefore judge voice experiences as much by “do I trust this?” as by “does it work?”

Security concerns include accidental activation, unauthorized recording, replay attacks against voice biometrics, and misuse of stored audio. Privacy concerns include retention, secondary use for model training, and sharing with third parties for analytics. Our stance is pragmatic: privacy is not a banner; it is an architecture. Data minimization, encryption, access control, and auditable retention policies must be part of the initial design, because retrofitting trust after a controversy is far harder than building it from the start.

Consent needs to be understandable

Voice consent prompts should be short, plain-language, and reversible. When users cannot tell what is captured and why, they assume the worst and adoption suffers accordingly.

4. Real-world limitations: accents, dialects, background noise, specialized vocabulary, and connectivity

Voice systems fail in ways that feel personal. A misrecognition can sound like disrespect to a user whose accent is repeatedly mishandled, or like incompetence when the system cannot understand domain terms that are central to a job. Background noise can make a competent model look broken, and intermittent connectivity can turn a cloud-dependent assistant into a silent brick.

In our implementations, we treat these limitations as design inputs, not as defects to apologize for later. That means environment testing, fallback interactions that do not require perfect speech, and careful feature scoping. It also means telling the truth: if a workflow depends on stable connectivity, we either build offline modes or we do not promise uninterrupted voice control. Users forgive constraints; they rarely forgive surprises.

Operational monitoring is non-optional

Even well-tuned systems drift as vocabulary changes and environments shift. Continuous monitoring of failure patterns, plus a safe deployment pipeline for model and grammar updates, keeps voice experiences from silently decaying.

TechTide Solutions: building custom voice-enabled software tailored to customer needs

1. Discovery and solution design for voice-enabled products aligned to real user workflows

Our voice projects start with discovery because the biggest failures are rarely algorithmic; they are mismatches between what users say and what the system expects. During workshops, we map user journeys, identify where hands-free interaction truly helps, and catalog the vocabulary users actually use—slang included. We also look for moments of risk: identity verification, sensitive data entry, and irreversible actions.

Solution design then turns those findings into an architecture choice: on-device vs. cloud, streaming vs. batch, transcription-first vs. intent-first, and how voice integrates with existing systems. We write conversational specifications the way other teams write API specs: prompts, confirmations, failure modes, escalation rules, and observability hooks. That document becomes the contract that keeps engineers, designers, and stakeholders aligned.

We prototype with real audio early

Scripted demos hide problems. Early prototypes built from real recordings (with proper consent) reveal noise issues, ambiguous phrasing, and edge cases that would otherwise surface late when changes are expensive.

2. Custom development and integration across web apps, mobile apps, and connected devices

Development is where “voice” stops being a feature and becomes a system. We integrate speech services, build NLU layers, connect to business APIs, and implement conversation state management. For IoT, we add device discovery, capability modeling, and secure command execution so voice actions map cleanly onto real device state.

Integration is often the hardest part because voice spans stacks. A mobile app might capture audio, a cloud service might run recognition, another service might handle user identity, and an enterprise system might execute the action. We design with explicit contracts and fail-safe behaviors: timeouts, retries, idempotent actions, and user-visible confirmations. The goal is predictable behavior under stress, not just success during a calm demo.

Observability is built in, not bolted on

We add structured logging around turn-taking: what the user said (or what the system thought they said), which intent was chosen, which backend calls were made, and how the system recovered from uncertainty. That telemetry is the difference between guessing and improving.

3. Testing, security, and scaling for production: accuracy tuning, privacy controls, and performance

Production voice systems demand a different test mindset than typical UI features. We test with varied audio conditions, speaker diversity, and realistic background noise, then evaluate not only recognition outcomes but also conversational success: did the user finish the task without frustration? Load testing matters too, because voice experiences degrade sharply when latency spikes.

Security and privacy are treated as first-class requirements. We implement access control, retention policies, redaction where appropriate, and clear consent UX. On the scaling side, we plan for growth in traffic and vocabulary, plus model updates that do not break established workflows. Accuracy tuning becomes an ongoing practice: monitoring unknown intents, expanding domain terms, and improving confirmations where errors cluster.

Our definition of “done” includes trust

A voice system that works but feels creepy will not survive. We therefore test privacy perceptions through UX reviews, ensuring users can tell when the microphone is active and what happens to their data afterward.

Conclusion: planning a practical voice technology roadmap

1. Prioritizing use cases that solve real business needs rather than adopting trends

Voice technology planning should start with friction, not fashion. The best candidates are workflows where typing is slow, hands are occupied, or speed matters more than visual precision. A roadmap built around real operational pain—documentation burdens, call deflection with good escalation, field workflows, or device orchestration—has a much higher chance of sticking than a roadmap built around “we should have a voice assistant because competitors do.”

At TechTide Solutions, we recommend writing a simple use-case thesis for each candidate: what job gets easier, what risk is introduced, and what success looks like in lived experience. When teams can articulate those points clearly, scope decisions become obvious and stakeholder alignment becomes dramatically easier.

Start narrow, then expand with evidence

Voice systems learn from use. Launching with a small set of high-confidence tasks lets teams build trust, collect feedback, and expand safely rather than overpromising from day one.

2. Preparing for adoption with data readiness, governance, and clear CX outcomes

Adoption is not just a launch event; it is a relationship between users and a system that must earn credibility. Data readiness includes domain vocabulary, labeled intents where appropriate, and integration access to the systems that actually execute actions. Governance includes privacy policies, retention rules, and clear ownership for model updates and incident response.

Customer experience outcomes should be defined in human terms: faster resolution, fewer handoffs, less repetition, more accessible completion paths. When teams only track technical metrics, they often miss the moment when users quietly stop using voice because it feels unreliable or intrusive. A well-run program couples technical evaluation with experience measurement and continuous iteration.

Governance accelerates delivery

Counterintuitively, strong governance often speeds teams up because it removes ambiguity. When data handling rules are explicit, engineers can build decisively without fearing late-stage compliance surprises.

3. Moving toward more natural, no-touch experiences as voice-enabled systems mature

Voice technology is steadily moving from command-and-control toward more contextual, multimodal interactions where speech complements touch, vision, and automation. In that future, the most successful systems will be the ones that understand not only words, but also intent within context—without overstepping privacy boundaries or pretending to be human.

So where should a business go next? If we were planning your roadmap with you, we would start by selecting one workflow where voice can remove friction immediately, then build a measured pilot with clear trust signals and operational metrics—because the real question is not whether voice is possible, but whether your users will choose it when it matters most.